What is Neurofeedback? Clarifying misconceptions of an evidence-based brain training technique

October 17, 2018 - neurocare group

What is Neurofeedback? A brief history of “brain training”

Neurofeedback was first explored in the 1950s and ’60s through the efforts of Dr Joe Kamiya and Dr Barry Sterman. Dr Kamiya had discovered that by utilizing a basic reward system (called ‘operant conditioning’), individuals could learn to change their brain activity. Similarly, Dr Sterman undertook an experiment to see if sensory motor rhythm (SMR) activity could be increased in cats via Neurofeedback. A basic machine provided a food reward every time a cat could change this brain activity, and many quickly learned to regulate their brain activity in order to get the reward. As a result of these initial studies, further work was undertaken to investigate Neurofeedback as a therapy to help epilepsy – with promising results.

In the mid-1970s, Neurofeedback began to grow in popularity among those outside the scientific realm. Some began to push Neurofeedback as a tool to aid meditation and spiritual growth, and it slowly became regarded as a ‘fringe’ methodology. Throughout the late 80s and into the 90s a number of researchers pushed on with efforts to explore clinical applications of Neurofeedback in areas such as ADHD, depression, anxiety and even within elite sports and performance enhancement. Since this time, our scientific understanding of the brain has changed and we are now more familiar with the ‘neuroplastic’ properties of the cells within the central nervous system. This has led us to a greater understanding of the process by which neurofeedback works. Even so, with more and more research coming to light with each passing year, there are still many in the broader scientific community who view Neurofeedback as an unvalidated methodology without sufficient support or clinical evidence. Some would say this may be in part caused by those who make misguided claims about the applications and properties of neurofeedback, given that there are many different versions and technologies available – with varying degrees of quality control and assurance of correct training by the practitioner.

Today, Neurofeedback has been validated by a number of large studies as an effective therapy to help people of all ages with ADHD or related symptoms, without side-effect and with long-lasting sustainable effects after the therapy program has ended. It is important to note as well that these scientific studies have ruled out placebo effects, and have made other standard measures to validate the statistical claims made so that it can be properly scrutinized against other therapies for ADHD. (See Strehl et al. 2017 and Van Doren et al. 2018 as recent examples of such studies).

How Neurofeedback works

The research and training teams working with neurocare group ensure that Neurofeedback practice adopted in our clinics or promoted in our training courses, follow evidence-based and standard protocols which have been properly backed by multicentre studies and are deemed effective in a clinical setting. These ‘protocols’ refer to the specific targeting of certain brain frequencies and the location from which they are recorded and fed-back. Monitoring, analysis and feedback of brainwaves or EEG are no longer ‘experimental’ but is common practice in assessing the function of brain activity. Patterns in the EEG are known to reflect states of activity at the brain level, which can provide insight into a range of cognitive states relating to attention, memory and mood. This is why it is important for us to make a QEEG assessment before starting any Neurofeedback program with a client. Whilst there are numerous and ongoing efforts to explore the outcomes of various neurofeedback protocols in experimental settings, it is important that when operating in a clinical setting the administrator only applies those protocols which have evidence regarding their specific claims and expected outcomes.

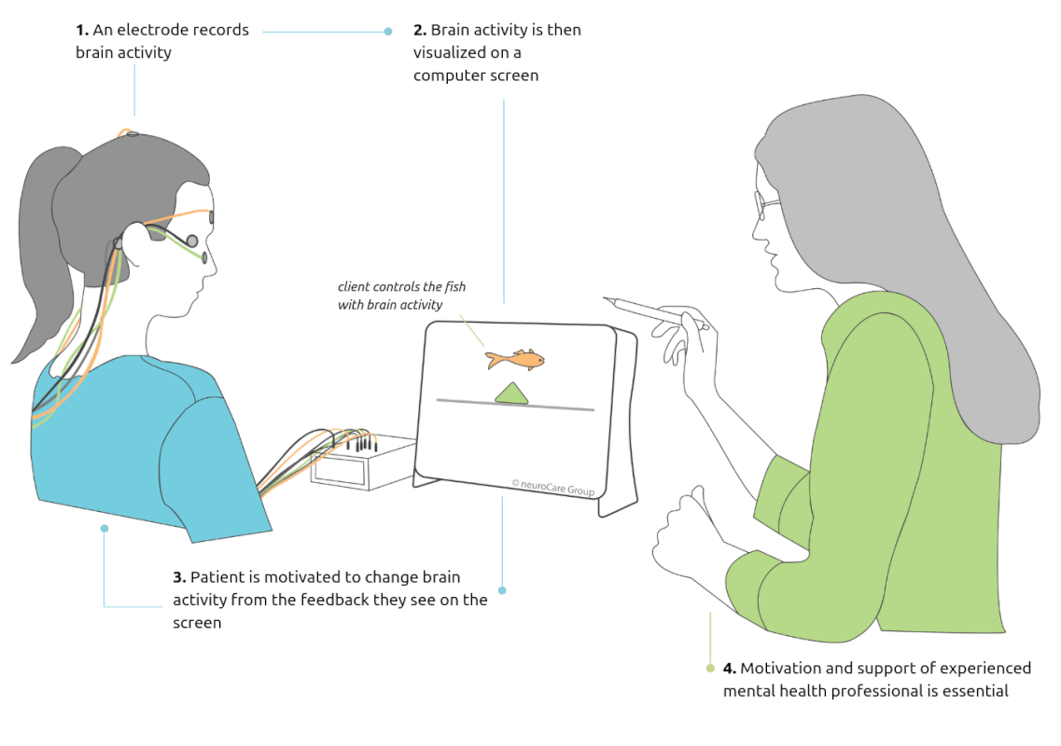

What is Neurofeedback? This example illustrates what is involved in the specific and evidence-based protocol of Slow Cortical Potentials (SCP) Neurofeedback, which trains the brain to voluntarily switch between an alert state and a more relaxed state.

What is Neurofeedback? This example illustrates what is involved in the specific and evidence-based protocol of Slow Cortical Potentials (SCP) Neurofeedback, which trains the brain to voluntarily switch between an alert state and a more relaxed state.

There are varying degrees of training out there for therapists offering Neurofeedback. Therapists offering Neurofeedback should have received BCIA and should understand and refer to the ever-growing collection of thoroughly conducted research. A provider must also be confident in the quality of the equipment they have purchased and that they are trained to correctly place electrodes and correct for interference in signal quality. A quick Google search can uncover a number of Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) toys, which may pick up on signals (not necessarily accurately recorded brain activity) to control a range of devices in fun and interesting ways. These devices are better described as toys and are unproven as clinical interventions.

Ongoing research has been able to highlight the validity of some of the most well-researched neurofeedback protocols and approaches. Whilst research has been undertaken to explore neurofeedback protocols to treat other cognitive and mental health issues, mixed or non-significant results have limited the scope of application. Over the years, three separate protocols have emerged with sufficient evidence as effective protocols for the treatment of ADHD. The Theta-Beta ratio, often considered a potential biomarker indicating the possibility of ADHD [1] is shown to be successful in improving ADHD symptoms of inattention and impulsivity. Similarly, the “up-training” of Sensory-motor rhythm (SMR) activity has been found to overlap with the cortical activity which can aid sleep issues which often underlie ADHD-like symptoms [5]. Finally, a more recent protocol, Slow-Cortical Potential Training (SCP) has been found to facilitate the ability to switch between states of activation and relaxation in children and adults with ADHD symptoms, leading later into the reduction of ADHD-like symptoms [3][4].

While we cannot discount the importance of ongoing work evaluating the outcomes of other neurofeedback protocols, it is important that clinical application of neurofeedback sticks to those protocols that are clinically validated. In doing so, not only can we maintain the growth of reputation for quality within the field, but also ensure that outcomes and expectations for clients are held to the highest standards.

Recommended questions to ask any Neurofeedback provider

-

Is the Neurofeedback provider licensed to practice and treat ADHD?

-

Is the equipment you use tested in scientific studies which show the efficacy of Neurofeedback?

-

Will you do a QEEG assessment to inform the protocol you use in my Neurofeedback program?

-

Is the specific Neurofeedback protocol you have chosen for me or my child validated by scientific research? (i.e. Theta/Beta training, SMR training, SCP training)

References

- Arns, M., Conners, C.K., & Kraemer, H.C., (2013) A decade of EEG Theta/Beta Ratio Research in ADHD: a meta-analysis. J Atten Disord; 17(5):374-83

- Strehl et al. (2017) Neurofeedback of Slow Cortical Potentials in Children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Multicenter Randomized Trial Controlling for Unspecific Effects.

- Kaiser, D., Othmer, S., (1999) Effect of Neurofeedback on Variables of Attention in a Large Multi-Center Trial. Journal of Neurotherapy

- Mayer K., Wyckoff, S.N. & Strehl, U. (2013) One size fits all? Slow cortical potentials neurofeedback: a review. Journal of Attention Disorders.

- Arns, M., Feddema, I., & Kenemans, J. L. (2014). Differential effects of theta/beta and SMR neurofeedback in ADHD on sleep onset latency. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, 1019. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.01019